Losing my son

On October 20th, my seven year old son Nikolas suffered cardiac arrest while undergoing a procedure at the hospital to treat an underlying congenital condition. The doctors performed CPR and succeeded in reviving him but ultimately he suffered catastrophic brain damage. My wife and I were in the hospital for nearly a month at his bedside as we awaited his ultimate prognosis.

What is there to say?

First, I'm devastated.

Second, I'm not going to be giving more details beyond what I write here for now.

Third, I'll address those the most common questions, and concerns.

Fourth, I'm making major changes to my life.

Fifth, I will describe a bit about what this situation feels like from the inside. If you have not experienced this kind of tragedy, it will likely surprise you, as it did me.

Devastation

There's three things everybody says to me now:

"I can't imagine what you're going through."

"I don't know how you're handling it."

"That must be so hard."

These statements are true. If you haven't been through this, you don't get it. So let me tell you all about it. It'll be okay. Well, actually it's not okay, but it's okay that it's not okay.

My son is alive, but all of his higher mental functions have been wiped out. He still sleeps and wakes, breathes under his own power, and responds to certain stimuli, but he makes no intentional movements. He moves reflexively, and occasionally smiles and even laughs, but he can't speak and it's not clear what degree of awareness he still has of his situation, if any. The MRI results were conclusive that the damage was widespread and severe, and to such a degree that short of an outright miracle, there is no hope for regeneration through brain "plasticity" or any other known path towards recovery. People don't come back from this kind of injury.

That's important to say. I believe in miracles, but part and parcel of that belief is the acknowledgement that miracles are by definition rare, and the faith that God is able to grant them must be paired with a complete lack of presumption of receiving one (Daniel 3:17-18, emphases mine):

17 If it be so, our God whom we serve is able to deliver us from the burning fiery furnace, and he will deliver us out of thine hand, O king.

18 But if not, be it known unto thee, O king, that we will not serve thy gods, nor worship the golden image which thou hast set up.

I would be delighted to hear Nikolas' voice calling out to me tomorrow morning, but I hold no lingering hope that this will happen. That's what it takes to get me through my day.

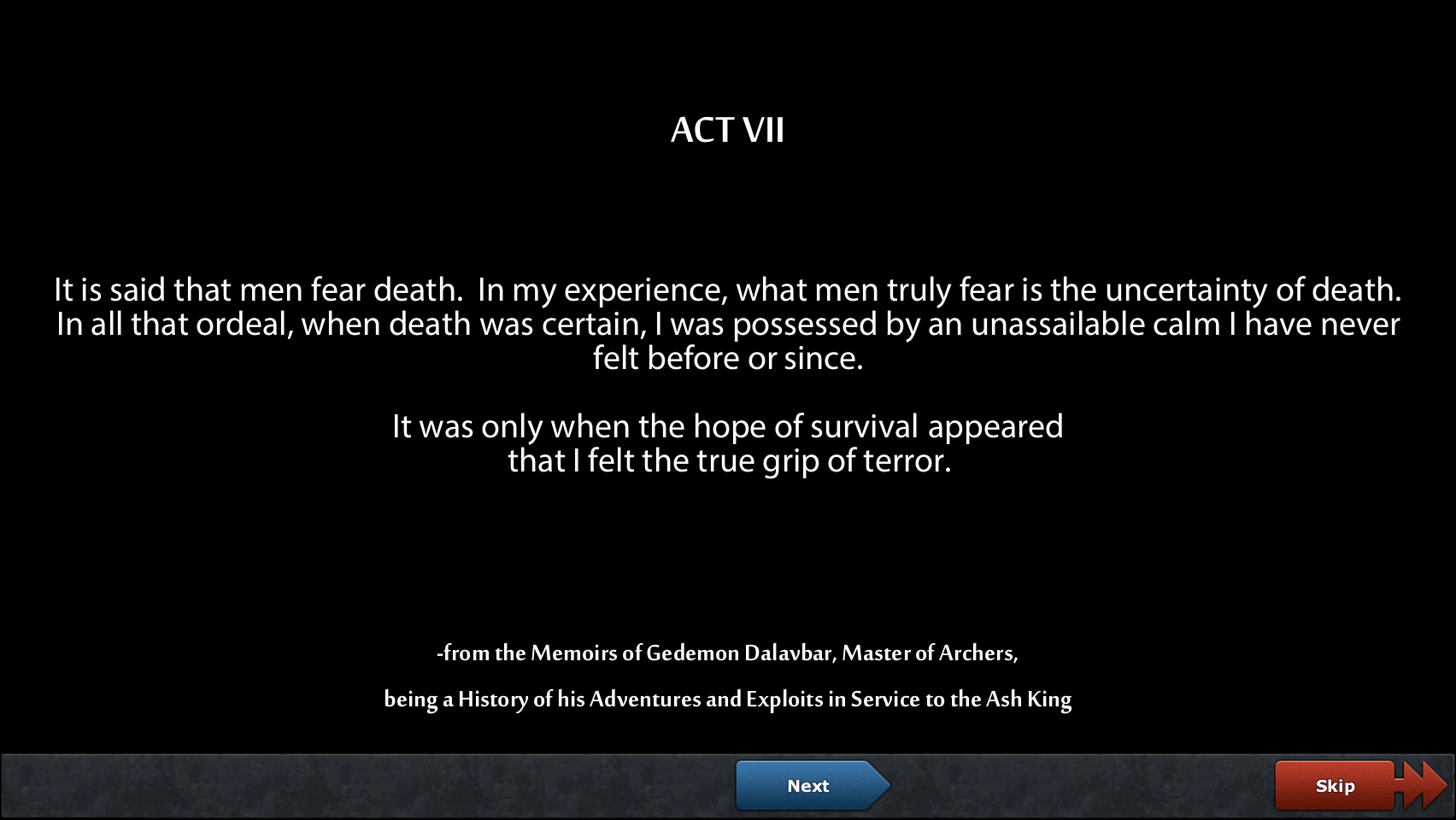

I'm reminded of one the little flavor quotes in Act VII in my game Defender's Quest: Valley of the Forgotten:

My friend James Cavin, the game's writer, wrote those words over a decade ago, and I couldn't think of a better way to describe the strangeness of my current situation.

While hope yet remained, I suffered the most. The most devastating moment in the hospital was opening the MRI report. Up until then we were clinging to hope, and afterwards there was nothing left to do but to live with the loss. Our crushed hopes allow us to get on with the long road ahead.

As for "I can't imagine how hard that must be"–

Turns out, unfathomable tragic loss isn't very hard. It's easy, in fact. Easy in the same way that falling off a cliff is "easy"–gravity does all the work for you. It's not like climbing mount Everest, desperately putting one foot in front of the other. It's not like struggling to answer questions in a final exam. Tragic loss is just something that happens to you.

It's not hard, just terrible.

The grief is different than people expect, too. I cried a lot, but after a certain point you only have so many tears left to cry. I can't cry all day, every day, for months on end.

And honestly, at this point crying feels good. Crying isn't really when I feel like I'm suffering the most, although I think people on the outside sort of had that expectation. There's this implicit assumption from other people that you will have a very legible grief, to "put on sad-face," so to speak.

But!

This isn't one of those essays where the author describes their personal suffering in great detail and then passively aggressively berates all the readers who haven't suffered to the exact same level for being somehow morally deficient, as has become vogue in the popular press over the last ten years.

Because guess what – two months ago I would have been just like most of you! Two months ago, if I were talking to someone who was in the position I find myself in now, I'd ask all the same "insensitive" and "inappropriate" questions, all the while being desperately afraid I was being insensitive and inappropriate. So everyone should just relax. I lost my son, it's terrible. No, you're not a bad person for asking me how I'm doing. Yes, everything's weird. I know you don't know what to say. I don't know what to say either. Nobody does. It's fine.

What We're In For

My son is alive, severely brain damaged, bedridden, and unable to care for himself. We took him off of all medical supports and moved him into home hospice care. This means that we stopped the artificial ventilator and IV's, as well as all medicines and treatments other than those aimed at comfort and pain relief, and moved him into a hospital bed we have installed at home.

The doctors initially thought he would quickly die after being taken off the ventilator, but he has persisted for about a month now. He receives food and water through a feeding tube, medicine for pain relief and comfort, and daily care from my wife and I as well as from hospice nurses who visit during the week.

The fact is, Nikolas could very well live for years or even decades to come, and my wife and I will take care of him up until that moment. We do not stand for euthanasia, but neither will we prolong his life through heroic and artificial life support measures. Food, water, comfort, and daily care–these he will receive from us, indefinitely.

This is not the sort of thing that can be easily outsourced unless I were to commit my son to a facility, which we will not do as it would drastically reduce our ability to see him on a daily basis. This puts a large daily burden of work, material expense, and restriction on personal freedom. We take this burden gladly.

Fortunately, we have been able to qualify for public medical assistance in this regard and it looks like we are going to be financially okay for the time being. I am grateful that I also have a strong private support network should I have to lean on it. To be 100% clear, I am not asking for money and I neither need nor want anyone to offer me any.

Changes

My nearly complete game, Defender's Quest 2: Mists of Ruin was originally supposed to ship at the end of 2023, but that's now been obviously delayed. I'm very grateful to our publisher, Armor Games, for being understanding in the midst of this tragedy.

A couple things are changing from the original plan before this all happened.

First, this is the end of my professional game career. There will be a lot I have to say about this in the future, but the short version is with all the obligations I now have (particularly ongoing medical expenses) I am suddenly in the need of a much more stable, predictable, and boring career. I was successful early on, but as the years went by I found myself having to juggle development with any number of day jobs and side gigs due to the inherent instability of indie game development. I've loved my time in games, but I have to move on. I will write a post-mortem of my 10+ years in games sometime, as I have had some real accomplishments above and beyond the two Defender's Quest games that I am quite proud of to this day.

Second, I am no longer a daily member of the DQ2 development team. This is particularly painful for me given that I was nearly at the end of a ten year journey for a game that's been in development since before any of my three children were born, but losing one of those children has upended my priorities.

But DQ2 is neither cancelled nor abandoned.

It was always Level Up Labs, LLC, not Lars Doucet, who bore the ultimate responsibility for the game's development, and I am but a part of that company. My co-founder, Anthony Pecorella, has heroically stepped up to the plate and coordinated the final stages of development in my absence. I am still in an advisory role and will make sure the final game is a good one, but I simply no longer have the capacity to do this with the new daily burdens in my life. I will try, if possible, to make sure we fulfill all of the pre-order campaign obligations (I've kept all the records), but I will ask for people's understandings if we fall short in certain regards or some of the goodies wind up being delayed.

As always, if you are unhappy with your preorder for any reason, email leveluplabs@gmail.com and we will cheerfully refund your money.

Third, GameDataCrunch.com is officially defunct for good, at least under my direction. I still have all the source code, scripts, databases and other stuff for it, so anyone with decent web development skills (it's mostly just a pile of php, javascript, cron jobs, and MySQL) could easily resurrect it and keep it going. I have some people in mind for this already, but if you want to make your own pitch for why I should turn it over to you I'd be more than happy to hear it: email me at lars dot doucet at gmail dot com.

Fourth, I now have one and only one job, which is working on real estate mass appraisal valuation technology for the purposes of accurately and credibly measuring the value of land separately from buildings and improvements. This is the kind of straightforward, steady, stable, boring work that I need to support my family right now. It also conveniently lines up with my niche interests.

And with that, I'm left with the new normal.

It's Strange

I'm shocked at how quickly our family adapted to the situation. Our two girls (ages five and ten) have proved remarkably resilient, and help with Nikolas' daily care with eagerness and calm. We still read to him at bed time, pray with him, and sing his favorite songs. I know that he almost certainly can't hear us in his current physical form, and though I don't know how eternity relates to the physical world that's welded to the arrow of time, I like to think that Nikolas watches us from Heaven and hears us in that way (and perhaps I am watching there alongside him from the other side).

The best metaphor I can give for the daily home hospice care of your own seven year old son is a monastic vocation. It's menial work, tied to the hours of the day, an obligation and an obedience, for the rest of my life, or his, whichever comes first. Nikolas has becomes a living altar to his own memory.

I do not want to paint an overly rosy picture. I re-experience the trauma of losing him every time I see him, and it is deeply painful to see him in his reduced state. But all I have left to give him is my love, expressed in his daily care.

There are many costs, and not just in terms of time and money. My wife and I can no longer leave the house at the same time without finding someone with adequate training to watch over Nikolas while we are gone. I'm grateful that we were fairly boring homebound personalities, as this means we have been forced to give up much less than other couples would experience in this situation.

I won't be traveling much in the future, for obvious reasons, but we will find a way to make the most essential trips should the need arise.

The other thing I want to convey to people is that although I'm sad and experiencing a great loss, I cling relentlessly to joy. Since I was a small child I always hated a particular kind of tragic story, and I still feel that way today. I did not hate tragedies in general, or any story with a sad ending, but specifically the kind of story where not only does something terrible happen to beloved characters, but the kind of story where it's very obvious that the author is making some kind of nihilistic statement in doing so, sort of turning to face the reader, saying, Now do you see, you naïve moron? Life is naught but pain, and you're a fool and a worm for not being as miserable as me!

Enough.

Look, the news media inundates us every day with endless tales of genuine horror and suffering, because in a world with billions of people that will always be happening somewhere. Life is and will always be fundamentally unfair, and the vale of tears filled with a never-ending parade of horrors. And yet, it's also true that for the median person on Earth, life is much better today than ever before in human history.

My own story is exactly one such example – the fact that I'm devastated to lose my son to a crippling injury highlights another fact–that this very thing has become so rare in my country as to be "unimaginable." We should rejoice at this! Losing a child used to be so unremarkably commonplace that everyone, even emperors and kings, routinely suffered it until approximately yesterday.

The correct adjective for the tragedy I'm experiencing is not "unimaginable" but unfathomable. I can imagine it just fine because it's happening to me, and you can imagine it too now because I'm describing it to you. And because we can imagine it, we can turn and face it, and, with God's grace, we can lift up our cross and bear it, somehow.

But what none of us can do is to measure–to fathom–the depth of it.

Stand at the brink of the abyss of despair, and when you see that you cannot bear it anymore, draw back a little and have a cup of tea.

— Elder Sophrony of Essex