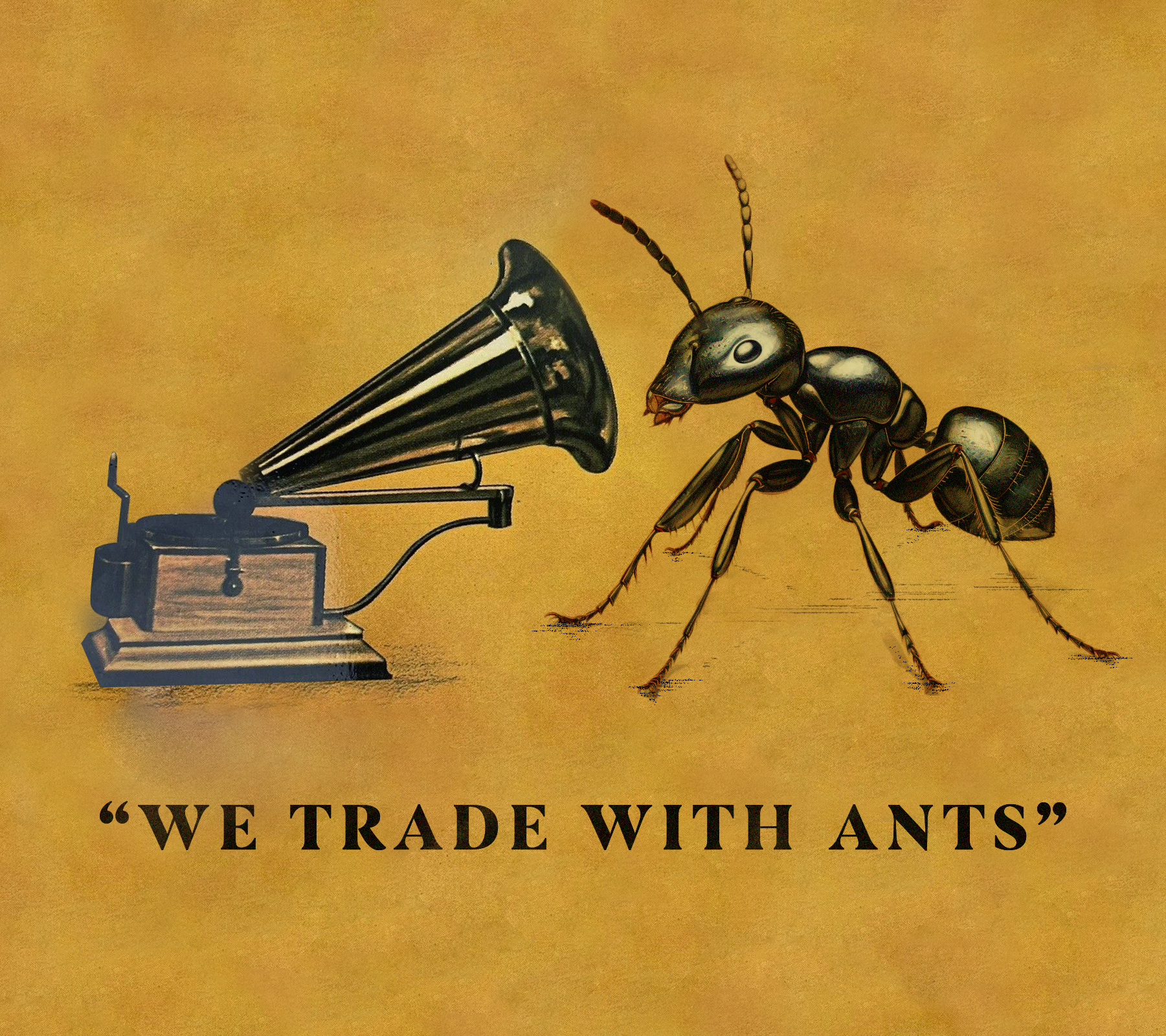

We Trade with Ants: From the Notebook of Anastasia Demoupoulous

We "big speakers" keep projecting our human minds on them, and the "little speakers" keep projecting their ant mind on us. This is the problem.

This is the latest entry in a series of short stories.

Previous chapter: Plague

Recap: Last time, protagonists Jeff Boudreaux and Anastasia Demoupoulous were shocked to discover that the ants were suffering from a mysterious plague. Faced with this crisis, they were forced to bring in trusted friend and entomologist, Kevin Zhang, to save the day. In the aftermath the ants' were identified as a new species, Camponotus Sapiens, and Kevin recommended moving the ants to a bigger and more private piece of land where they could be expand, thrive, and be properly studied.

The following is a verbatim transcription from the research notebook of Anastasia Demoupoulous , written just before the relocation.

Alright, notebook. Time to vent. While I’m extremely humbled and astounded at the task set before me, in the privacy of these pages at least I AM GOING TO COMPLAIN A LITTLE.

Precisely because the ants are intelligent, and because we can speak with them, they are immensely frustrating to deal with. You think you’re talking to another person on your own level, but you keep forgetting that the other person isn’t human. Maybe this is kind of like what having children is like–you keep projecting adult expectations on someone who is fundamentally not capable of that (maybe I'm starting to understand my mother a bit more). But children eventually bridge that gap, whereas I expect even after decades of study, a gulf will forever remain fixed between the ants and us.

The real problem isn't the gap itself, it's that both sides just can't resist constantly papering over it and pretending it's not there. We "big speakers" keep projecting our human minds on them, and the "little speakers" keep projecting their ant mind on us. This is the problem.

As the resident language expert, it's also my problem, because my job is establishing and refining communication protocols. Here are my top three gripes:

Verbs suck

Nouns are the easiest thing to introduce. You put something on the naming plate, suggest an identifying set of phonemes, and wait for the ants to respond. If they get confused you repeat yourself a couple times, or switch up the context a bit. But usually they catch on quickly. You say, "Here’s a thing, I call it such-and-such." They say: "We hear you. This is such-and-such." It's all very concrete and direct. Very little abstraction.

Adjectives are harder, but not too bad. Once you’ve taught them seed or fruit, all you need to do to teach them “big” is to repeatedly show them a big seed and a big fruit enough times that they understand the phoneme big always shows up alongside a big version of something they already know the word for.

You’d think prepositions would be too abstract, but actually they seem to get those pretty naturally too! Fruit under wood. Seed on top of brick. Honey inside of shell. Lay it out for them, and say the words, and they get it. They're always thinking about where things they want are located and how to get to them, so position and spatial relations are much easier for them to grasp than you might expect. You just drill the examples and repeat the words, and eventually they understand.

You can even quiz them! Set up a scenario and ask them to fill in the blank. Once you've taught them the prepositions, you can present them with phrases like Fruit (pause) wood, question-mark? Or: seed (pause) brick question-mark? The scouts come back, they find the thing, they go back into the nest, they think for a good long time, they give you an answer word, and you say yes or no. Repeat. Repeat. Eventually they understand.

But verbs! Confounded, terrible, accursed verbs! They suck so much!

The "show and tell" game we use to teach the ants new words works really well for things, and much worse for actions, because of the vast differences in scale and perception between our two species.

The ants don’t stand even a quarter inch tall, which means at a conservative estimate I’m two-hundred-and-forty-four times taller than them. In their eyes I am a towering titaness, a cloud-dwelling colossus, a gigantic giantess, a...

Sorry, I got carried away there for a minute. Anyways, I’m tall and mighty and they’re itty-bitty (and cute). They can’t even see me, let alone my movements, so I can't show them any action. Even if I could, they would have precious little frame of reference for it. They’ve let slip several times that they assume we "big speakers" are made of ants, too, just giant ants that are too big for them to see directly. When George “met” them that one time by placing his thumb on the naming dish, the moment they first identified him as "big speaker," they thought his thumb was just the end of the colossal antennae of one of his “workers!”

My point is, I can’t just pick up a cookie, say the word “eat,” and put it in my mouth and start chomping away. Instead, I have to get the ants to do something, send them a message with my intended word for that action, and just hope the ants understand. From what I can make of George’s notes, nailing down verbs took easily ten to one hundred times as much time and effort as the next most difficult parts of speech did.

In so many ways we are standing on my dear old Papou’s shoulders. The hardest verb to bootstrap by far had to be the very first one, and how he pulled that off from scratch, I can only guess. Sure, he describes the procedure in his notes, but how many countless hours, or days, or weeks, did it take to get the ants to finally get the idea at all? How many dead-ends and failed attempts did he leave out?

For instance, he has an entire chapter detailing the countless days he spent just trying to clearly distinguish eat from get. I can’t imagine how hard my work would be if I couldn’t even take those particular words for granted.

Verbs suck.

Counting sucks

George never taught the ants how to do math, so we have to do it and it’s really hard.

For one, they use base six (mostly). Six seems to be the largest integer that an individual worker's tiny brain can recognize, at least according to Kevin and his behavioral studies.

We established a word for “group” with them (or maybe just “pile”, if I’m being honest), and they started using it as an affix. So they’ll say six-pile-two. I have a pile of six things and then two things, which makes eight things. If you’re patient enough you can specify some pretty big numbers this way. Six-pile-six-pile is 36. Six-pile-six-pile-six-pile is 216.

Is it because they have six legs? Or is that just a coincidence? In any case, six seems like the upper limit for their base system.

I say "upper limit" because they only mostly use base six. Also I lied, it's not “base” six, because it's not really a base system with proper place value at all. That's because they will pick custom pile sizes every now and then, so sometimes they will say three-pile-two (meaning five), or five-pile-three (meaning eight). Maybe that's because down in the nest somewhere there is a literal pile they’re referencing, and it originally had five things in it, and just now someone added three to it, and now they’re telling us about it. Or maybe the particular ant who placed the actual pile and relayed the message about it up the chain of their “nervous system” had a brain that maxed out at five. I don’t know. Maybe Kevin can find out.

So, since piles can be of different sizes, you can wind up with situations where they say "4-pile-3-pile-5-pile-two." That means, "a pile, made up of four piles, each made up of 3 piles, each made up of 5 things. Plus two more things." So (4 x 3 x 5) + 2, or sixty-two.

I have begged and pleaded with them to standardize on six as the base pile size, at least when talking to us, so that we can get an actual place value numbering system going. This has not been a total failure but also not a smashing success. Also, I'm still trying to introduce them to the concept of zero, which remains an ineffable mystery that continues to intrigue and confuse them.

We also have to be careful about units. The ants are ruthlessly concrete, so “five” doesn’t mean much to them. Five what? Five apples? They understand what “apple”, the food material, is, but not what “an apple” is, for the simple fact that they have never in their entire lives ever experienced the basic phenomenon of “an apple,” only “some apple.” All they know is the part, they have never seen the whole.

We have to remember that they’re smaller than most things they interact with, whereas we’re usually bigger, or at least of comparable size, to the objects of our world. Everything humans might want to count, we can either hold in our hands, or point to with our fingers. Ants don't have hands or fingers.

To put this in linguistic terms, the ants have a very strong differentiation between count nouns and mass nouns. In English, count nouns are countable things you have a certain number of–five golden rings, three French hens, a partridge in a pear tree– but mass nouns are things you can’t count, you can only have a certain amount of them–four cups of flour, five liters of water, one gallon of milk, etc.

For ants the usual test is, can a single ant pick it up and move it without having to cut it into pieces first. The most familiar objects in this category are their own eggs and larvae, which they’re constantly attending to. Eggs and larva are countable, so when they talk about those they mean number of those things.

But say they find a juicy grasshopper, or an Oreo Cookie, or a nice fat grub. They literally can’t grasp it–not with their mandibles, and not with their mind. They either have to cut it into pieces, or recruit a team to lift and carry it back home together. In this case they switch to quantifying the object in terms of ants.

But the "size" they're measuring is not the size of the object, it's the size of the workforce. They’re not saying, “this cookie is 50 ant-loads big,” they’re saying “this cookie is a 50-ant job.” That’s because what's relevant to them is how many workers they think they need to recruit to get it back to the nest.

Which, okay, fine, but it’s a constant trap for us because there can be a very big difference between the absolute size of a thing, and how many ants they think they need to allocate to dealing with it on any given day.

As you can imagine, this means you need to pay extreme attention to detail whenever you use a number in a trade agreement. You not only have to constantly remind yourself to put things in terms of pile-able ant-loads, and you have to double and triple confirm that you and the ants are on the same page about the agreed upon quantities of whatever is at stake.

It’s just so easy to accidentally promise the ants “50 ant-loads of sugar,” when what actually got communicated was “a 50-ant job’s worth of sugar.” Given that the workers assigned to that task will be making multiple trips, that could easily amount to an error of 100 times or more, resulting in some very grumpy ants.

And don’t even get me started on communicating measures of liquids.

Returning to the subject of counting and measuring, the ants seem to have two completely separate systems for dealing with it. A fast intuitive system, and a slow rational system. They use their “body” (meaning masses of individual ants) for the fast system, and their “mind” (meaning whatever process governs their conscious thinking) for the slow system.

The “fast” calculations seem entirely unconscious, implicitly performed by pheromone trails and the same basic emergent ant swarm behavior that all other mute ants share with them. They probably don't even know they're counting and measuring, the same way we don't know the physics equations our bodies are implicitly solving to catch a ball or walk up stairs.

The “slow” system is when they use their collective “mind” to put numbers into words, using the same mind that talks to us, whatever that is. Kevin is still trying to work out the ant neurology that powers it.

So basically what this means is that the ants are very good at doing lightning fast implicit math in their sleep to dynamically allocate resource gathering and distribution across the nest, but very slow at answering the conscious question “what is two plus two,” because that requires a whole bunch of physical ant-to-ant signals to drive whatever underlying linguistic signal processing in their “brain” makes that happen.

Counting sucks.

Memory Sucks

The ants do not have great memories, and it’s easy to forget that.

Now, the kind of "memory" I’m specifically talking about here is what I'll be calling “high level” memories, ones that are the exclusive domain of the colony’s conscious mind, and not whatever information is stored in the brains of individual ants.

The unconscious colony as a simple collective has the same “low-level” memory capabilities that we see in regular mute ants–the ability to learn that a food source is here, or that there’s a threat or predator over there, and all that stuff. This is all the familiar ant stuff they already do with chemical signals and pheromones, and whatever is already within the cognitive grasp of individual ants. It's limited, but it's all there in Camponotus Sapiens just like in Camponotus Pennsylvanicus, and the myrmecology literature has that stuff well covered. That's not what I'm talking about.

“High-level” memories are the ones similar to what us humans have, and they belong exclusively to the collective colony-level “singular we” that talks to us. Those "high-level" memories come in two forms–working short-term memory, and long term storage. Both are quite limited compared to Humans.

Their limited working memory bounds the complexity of ideas you can communicate. For humans working short term bounds how much information you can take in and process at once, like a funnel that bottlenecks your brain. If three people try to hold a conversation with you at once, you're only going to be able to understand one of them. And if someone overwhelms you with a huge complicated info-dump, you might not understand it at all. On the other hand, you might easily grasp what they're staying if they structure the same ideas in a way that's easier to digest. The ants seem to have working memories that work exactly like this, but are much more limited than our own.

The big surprise is how much their capacity seems to fluctuate day to day. When we first made the water treaty with them, and when they alerted us about the plague, they were nearly communicating in paragraphs. We got used to that and started to take it for granted.

But soon we found that on many other days they would get confused if you sent more than a simple sentence at them, and their own responses became abrupt, short, and directly to the point. And distressingly, some days the ants would not communicate with us at all.

We were afraid this was another plague for a while, but the ants didn't seem concerned at all when we asked them about it on their more talkative days.

Kevin hypothesizes that the ant’s “mind,” whose physically substrate corresponds to some specific gathering of workers in the nest, has fairly plastic capabilities. In other words, most of the time the “mind” is switched off, “asleep,” if you will, and only when the need arises do the ants do whatever activity is required to “wake up” their conscious self.

If this is true, it might also suggest that they can actively control the amount of resources they’re allocating to thinking, and on days where they can barely string a single sentence together, their assigned “brain budget” is low, and on days where they’re positively Shakespearean, they’ve made thinking–and communicating–their number one priority, and allocated resources accordingly. This is in stark contrast to the way human brains work, which are always "on," and are constantly hungry for resources.

It’s a pretty good hypothesis, but we’ll have to wait for physical proof to back it up. In the meantime, I’m still stuck with my basic problem–getting a handle on whether the ants remember anything I told them yesterday or not.

From what I can tell, long term high level memory storage is actually fairly durable. If you tell the ants something, there is a very good chance they will successfully stash that information–they're often bringing up things first taught to them months ago (not to mention steadily learning the Humantish language itself).

But getting them to recall a memory at a time and manner convenient for us humans is another matter. If the mind is sleeping, obviously they won’t talk to us at all, and they won’t be doing any remembering either. And if the mind is awake but feeling lethargic, the memory might exist but the mind just won't try very hard to access it. The mind also doesn’t seem to be good at remembering things if it’s a "low brain budget" day, and the mind is currently “dumber” than it was on the day it stored the memory. A “smart” memory seems to require a “smart” mind to retrieve, but a “dumb” memory can be retrieved by a mind operating at any power level. Our early experiments suggest that the relevant criteria is the complexity of the memory itself.

There do seem to be two caveats to the above theory.

The first is that in order to remember something, the ants might have to actively choose to store that information. Humans, with our large luxurious brains, are constantly storing all kinds of memories, all the time, automatically. The ants, by contrast, seem to need to intentionally press “save” on anything they want to remember long term, or else it gets wiped the next time the mind goes to sleep. We learned that the hard way on days we had lots of long discussions with them, only for them to recall only about a tenth of it the next day. You can give them hints like “please remember this,” but ultimately they decide what they think is important themselves. There seems to be some cost to ‘writing’ a memory, but we have no idea how to measure or quantify that.

The second caveat is that long term memories seem to decay slowly over time. That’s not such a big surprise, humans are the same way. We have a hypothesis that actively getting them to recall a memory will strengthen it the same way it does in humans, and if that turns out to be true it would imply that we could use spaced repetition strategies to help them memorize key things we care about.

All this is to say that although the text-message interface often makes it feel like you’re talking to a human on the other side, you’re not. You’re talking to a sapient ant colony, and it has very real limits on its cognitive abilities.

Memory sucks.

Also This is Awesome

I know it's silly to complain and moan amidst all these incredible discoveries, but I just have to privately blowing off a little steam after another long day's work. I guess I'm also reminding myself how hard the work really is, and how little I can take for granted. After a long and frustrating day, I've found the number one skill I need to cultivate in dealing with the ants is patience.

The payoff is more than worth it, and I'm so grateful for the privilege of being their teacher. I don't deserve this and I just sincerely hope I don't do anything to screw this up and hurt the little speakers. I worry about that a lot.

I have to remind myself when I start feeling maternal that they’re not children, they're not human. They’re little aliens. But they have minds, and that makes them little people.

I love them so much.